Introduction

The main source of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is fossil fuels. While there is concerted global effort to produce alternative carbon neutral fuels, it will be a while yet before such fuels become fully available and accessible to ships. The need to decarbonise is urgent if the worst impacts of climate change is to be avoided. In line with the Paris Agreement goal, the EU and IMO have set ambitious targets to reach net-zero GHG emissions by, or in the case of the IMO, “by or around, i.e. close to”, 2050[1]. Members are directed to the Club’s article, A Roadmap for Ship Decarbonisation (ukpandi.com) for the Club’s discussions on the IMO’s initiatives. In this article, we will be looking at the EU’s initiatives, more specifically the framework of its emissions trading system as it relates to shipping.

The European Union's emissions trading system (EU-ETS)

EU-ETS is the world’s first emissions trading system and it remains the largest GHG emissions trading system across multiple countries and multiple sectors. Today, the system is aligned with the overarching EU climate targets. It is an emissions cap-and-trade system, meaning that a limit, or cap, on GHG emissions is set for certain sectors of the economy. The EU issues a limited number of EU allowances (EUAs) each year for each sector, with the number of EUAs available reducing year-on-year (see further below). Companies have to purchase sufficient EUAs to offset their annual GHG emissions which are subject to EU-ETS.

Each EUA gives a company the right to emit an amount of GHG equivalent to the global warming potential of 1 metric tonne of CO2. Methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) will be included in EU-ETS from 2026. As methane has a global warming potential 28 times, and nitrous oxide 228 times, that of CO2, 28 EUAs will have to be surrendered for 1 metric tonne of methane and 228 EUAs for 1 metric tonne of nitrous oxide emitted.

In 2021, EU-ETS was included in the EU’s “Fit for 55” package legislative proposals[2] and the system was extended to shipping from 1 January 2024. Including shipping in EU-ETS is expected to help the EU achieve its 62% GHG emissions reduction target for 2030, compared to 2005 levels[3].

To which ships does EU-ETS apply?

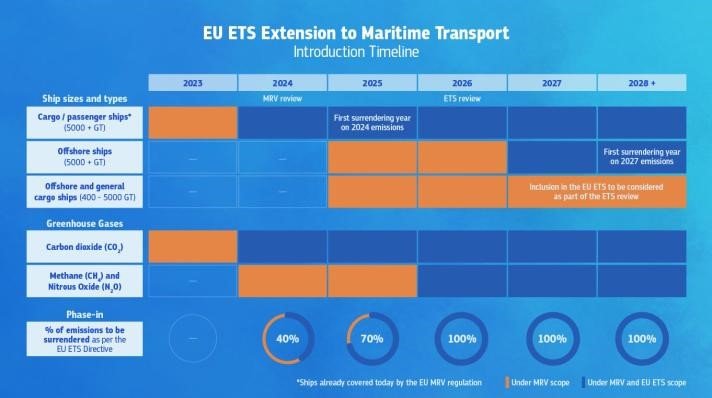

The EU-ETS applies as follows to all ships that are not excluded[4] or below the minimum size, and which enter EU ports, regardless of the flag they fly:

- Cargo and passenger ships of 5,000 GT and above must start reporting data to the EU’s Monitoring Reporting and Verification system (“EU MRV” – see further below) from 1 March 2024, and to surrender their first EUAs by 30 September 2025 for emissions reported in 2024.

- Offshore ships of 5,000 GT and above must start reporting data to EU MRV from 1 January 2025, and will be included in the ETS from 2027, with their first surrender of EUAs in 2028.

- Offshore and general cargo ships of 400 -5,000 GT must start reporting data to EU MRV from 1 January 2025 with their inclusion in the ETS to be reviewed in 2026.

These requirements are summarised in the table below taken from the European Commission’s Climate Action page:

Are all emissions subject to EU-ETS?

The answer is no, at least not initially.

The emissions which count towards EU-ETS are:

- 100% of emissions from intra-EU voyages;

- 50% of emissions from voyages arriving at an EU port from a non-EU port, or departing from an EU port for a non-EU port[5];

- 100% of emissions generated at berth in an EU port.

The percentage of emissions to be offset

The offset requirements will be introduced incrementally, with the EUA requirements increasing annually as below:

2025: 40% of emissions reported for 2024

2026: 70% of emissions reported for 2025

2027 onwards: 100% of reported emissions

Examples:

- In 2024, a cargo ship emits 100 tonnes of CO2 whilst loading and discharging within the EU. Although 100% of the emissions will count, only 40% of those emissions would need to be offset (i.e. 40 EUAs).

- In 2025, a cargo ship emits 100 tonnes of CO2 on a voyage from a port outside the EU to a discharge port within the EU. Only 50% (i.e. 50 tonnes) of the CO2 would count, and only 70% of the 50 tonnes would need to be offset (i.e. 35 EUAs).

- In 2026, a cargo ship sails from a port in India, discharges at a port in Greece, and at a second port in Italy. 50% x 100% of the emissions from India to Greece, and 100% of the emissions from Greece to Italy would need to be offset.

Note that the EEA countries, Norway, Iceland and Lichtenstein, have been included in EU-ETS and calls at ports in these countries are to be treated in the same way as calls at ports of EU Member States.

The EU Monitoring, Reporting and Verification Regulation

The EU MRV is a regulatory framework developed in 2017 to monitor and analyse GHG emissions from shipping activities within the EU. It required all ships over 5,000 GT that operate in the EU to monitor and report their fuel consumptions and emissions.

EU MRV was revised in 2023 to include maritime transport activities in EU-ETS. As of 1 January 2024, shipowners must report into the EU MRV platform verified[6] fuel consumptions and emissions of their ships between 1 January to 31 December of each calendar year, by 31 March of the following year.

By 30 September of the reporting year, shipowners have to surrender sufficient EUAs to off-set their emissions obligations under EU ETS.

EU Allowances (EUAs)

General EUAs are issued by the EU across the sectors. 80 million of these EUAs have been set aside for shipping in 2024. This number will reduce by approximately 4% year on year. Shipping companies will have to work out how many EUAs they will need to surrender to offset their company’s emissions for each relevant year. They will then select one of the three main options below for acquiring EUAs depending upon their needs and how much they are prepared to pay for the EUAs:

- From the primary market through auctions arranged by the European Energy Exchange (EEX) on behalf of the EU and its Member States where the EUAs can be purchased at a fixed price;

- On the secondary market where the EUAs are traded, with its price fluctuating according to supply and demand;

- In the futures market, if purchasing EUAs to meet future surrender obligations. Here, the EUA’s price again fluctuates depending on market expectations.

EUAs issued on or after 2013 do not expire and may be banked for use in future years.

Part of the revenues generated from the auction of EUAs will be deployed via the Innovation Fund to support the decarbonisation of the maritime sector, including ports.

Administering authorities and Maritime Operator Holding Accounts

An Administering Authority is the authority in an EU/ EEA Member State to which shipping companies have to surrender EUAs based on their emissions reported in the preceding calendar year.

On 31 January 2024, the EU issued an attribution list to inform shipping companies which Administering Authority they will have to deal when surrendering EUAs. Shipping companies registered in an EU Member State are automatically allocated to the Member State in which they are registered. Companies that are not in an EU Member State were allocated administering Authorities at places where their ships had called most frequently in the previous four years. The attribution list was prepared based on the best available information recorded by companies in the THETIS-MRV system and, for ports of call, as reported in SafeSeaNet.

Within 40 working days of the publication of the attributions list, a shipping company shall submit to the relevant national administrator information for opening a Maritime Operator Holding Account. Shipping companies not included in the attribution list have 65 working days from the date of the ship’s first port of call falling within the scope of EU-ETS to do so.

The attribution list will be updated every two years.

Who is the entity responsible for compliance with EU MRV and EU-ETS?

The responsible entity for compliance with EU MRV and EU-ETS can be either the shipowner (i.e. the registered owner) or the ISM company of the ship. For the ISM Company to assume responsibility for compliance, it will need to receive an express mandate from the shipowner (or the bareboat charterer, as agent for the shipowner).

The shipping company however remains the entity responsible for surrendering allowances. Nevertheless, the EU recognises the “polluter pays” principle i.e. those responsible for environmental damage should pay to cover the costs. Shipowners may therefore seek to recover their EU-ETS compliance costs from their charterers. BIMCO has produced several clauses to assist parties in their negotiations to allocate such compliance costs between themselves[7].

Valid port of call

A port of call for the purpose of EU-ETS is defined as “the port where a ship stops to load or unload cargo, to embark or disembark passengers, or where an offshore ship stops to relieve the crew”. Calls at ports for the following purposes fall outside this definition:

- for the sole purposes of refuelling,

- for obtaining supplies,

- for relieving the crew (other than an offshore ship),

- for going into dry-dock or making repairs to the ship and/or its equipment,

- because the ship is in need of assistance or in distress,

- ship-to-ship transfers carried out outside ports,

- for the sole purpose of taking shelter from adverse weather or rendered necessary by search and rescue activities,

- calls by container ships in a listed “neighbouring container transhipment port” (NCTP[8]).

Carbon leakage and neighbouring container transhipment ports (NCTPs)

The EU has designated certain ports as NCTPs in order to prevent “carbon leakage”.

An example of carbon leakage is as follows. A container ship loads cargo at Shanghai for discharge at Rotterdam. The shipowner calls at Tangier in Morocco to pick up more cargo before proceeding to Rotterdam. This is done to avoid paying for emissions on the voyage from Shanghai to Tangier, this being a voyage falling outside the remit of EU-ETS. The shipowner would instead only need to offset the ship’s emissions between Tangier and Rotterdam, this being a voyage falling within the remit of EU ETS.

To disallow the above, certain ports including Tangier and East Port Said in Egypt have been designated “neighbouring container transhipment ports” (NCTPs). NCTPs do not qualify as ports of call for containerships[9]. This disqualification of ports as valid ports of call only applies to container ships. As such, a bulk carrier from Shanghai may still discharge at an NCTP port prior to calling at an EU port, and only pay for emissions from the NCTP to the EU port.

The list of NCTPs will next be updated by 31 December 2025, and then every two years thereafter.

Failure to submit

EU Member States are required to set out penalties that are effective, proportionate, and dissuasive. In addition, pursuant to EU legislation:

- A failure by a shipping company to surrender EUAs will in the first instance result in a fine of €100 per metric tonne of CO2, with the liability to surrender the required EUAs remaining.

- A failure to surrender EUAs for two or more consecutive reporting periods may lead to the shipping company being refused entry to the ports of all EU Member States. If the ship is flying the flag of an EU Member State, and it enters an EU port, it may be detained until the company’s surrendering obligations are satisfied.

- Shipowning companies may also have their names publicised in the media.

Conclusion

The EU-ETS’s cap and trade system has shown itself to be successful in reducing GHG emissions from industry, electricity generation and aviation, and it is similarly expected to help reduce GHG emissions from shipping.

Further policies and initiatives are also being considered, in order to further reduce emissions. For example, EU-ETS is only targeting emissions from “tank to wake” whereas FuelEU Maritime, which will enter into force from 1 January 2025, will aim to promote the use of renewable and low carbon fuels and to incentivise the production and use of Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin (RFNBOs) by targeting emissions from “well to wake”. The intention is that these two EU initiatives will work in tandem to drive the changes needed for the EU to reach its stated target of zero GHG emissions by 2050.

In the meantime, improvements in the designs of ships and ship engines, the adoption of measures such as slow steaming, the harnessing of solar and wind power, the launch of financial, operational and consumer-focused initiatives such as the Poseidon Principles, green shipping corridors and the Blue Visby solution, are all contributing towards the elimination of GHG from shipping.[10]

Members may find the following links to the European Commission’s FAQs helpful for additional information on this subject but your usual contact at the Club will also be happy to assist you with any questions you may have on this subject.

---

[2] The EU’s “Fit for 55” package legislative proposals were adopted to help the EU meet its target of a 55% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 relative to 1990, and net zero by 2050.

[3] Directive - 2023/959 - EN - EUR-Lex (europa.eu)

[4] The following categories of ships are excluded: warships, naval auxiliaries, fish-catching or fish-processing ships, ships not propelled by mechanical means and government ships used for non-commercial purposes.

[5] The EU has indicated that it will consider counting more than 50% of emissions from voyages into or out of the EU, if the IMO has not adopted a global market-based measure by 2028.

[6] Ships’ emissions must be verified by verifiers accredited by EU Member States (i.e. National Accreditation Bodies).

[7] ETS - Emission trading scheme allowances clause for time charter parties 2022

ETS – Shipman emission trading scheme allowances clause 2023

ETS – Emission scheme freight clause for voyage charter parties 2023

ETS –Emission scheme surcharge clause for voyage charter parties 2023

ETS – Emission scheme transfer of allowances clause for voyage charter parties 2023

[8] A port is to be identified as a ‘neighbouring container transhipment port when this port meets three criteria set out in the ETS Directive: its share of transhipment of containers exceeds 65% of its total container traffic during the most recent 12-month period for which data is available; the port is located outside the Union but less than 300 nautical miles from a port under the jurisdiction of an EU Member State; the country of this port does not effectively apply measures equivalent to the ETS for that port.

[9] Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/2297 of 26 October 2023 identifying neighbouring container transhipment ports pursuant to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (europa.eu)

[10] Please refer to COP28 - A Summary (ukpandi.com) for a few of the shipping sector’s green shipping initiatives.