Background

In March 2020, the English Court of Appeal reached a verdict that attracted much attention. Addressing the grounding of the CMA CGM Libra, the court ruled that the vessel was not seaworthy at the time of the incident because the passage plan, made prior to the vessel’s departure from the port of Xiamen, was defective.1

This verdict came as a shock for vessel operators (Masters and officers) and Shipowners (ship management companies) around the world. The meticulous process required to prepare a passage plan for every voyage may be the reason the Court focused on these important, yet routine, tasks.

The judgment identified two problems concerning the passage plan:

1) The officer did not use as a reference the following information in the Notice to Mariners NM6274(P)/10 issued by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (no attention was paid to charts):

- The west side (outer side) of the channel was a danger zone.

- The depth was often shallower than indicated on the charts.

Note: The (P) in the Notice to Mariners stands for “preliminary”

2) The no-go area was not entered on the chart.

The ship’s Master was aware that some parts of the channel were shallow. As a result, the vessel departed from the channel but ran aground in a shallow area that was not on the chart.

The judgment also highlighted faults with the bridge team, but the principal problems were the shortcomings in the preceding two items. Incidents that occur when a ship is under way are normally treated as negligent navigation, however, in the judgment of this incident, rather than blaming the negligence of an officer, the focus was on the responsibility of the Shipowner due to their failure to fulfill the due diligence requirements prior to the voyage. Because of this, the vessel was deemed to be unseaworthy.

This document considers an incident presented to the English High Court in 2002, but in which judgment differs from this recent case. The judgment in the CMA CGM Libra case states that “a defective passage plan makes a vessel unseaworthy,” a conclusion that is certain to create concerns among officers and Shipowners. For the 2002 incident, the link between the passage plan and seaworthiness was not used for determining if the vessel was seaworthy.

We would welcome your opinions concerning this subject.

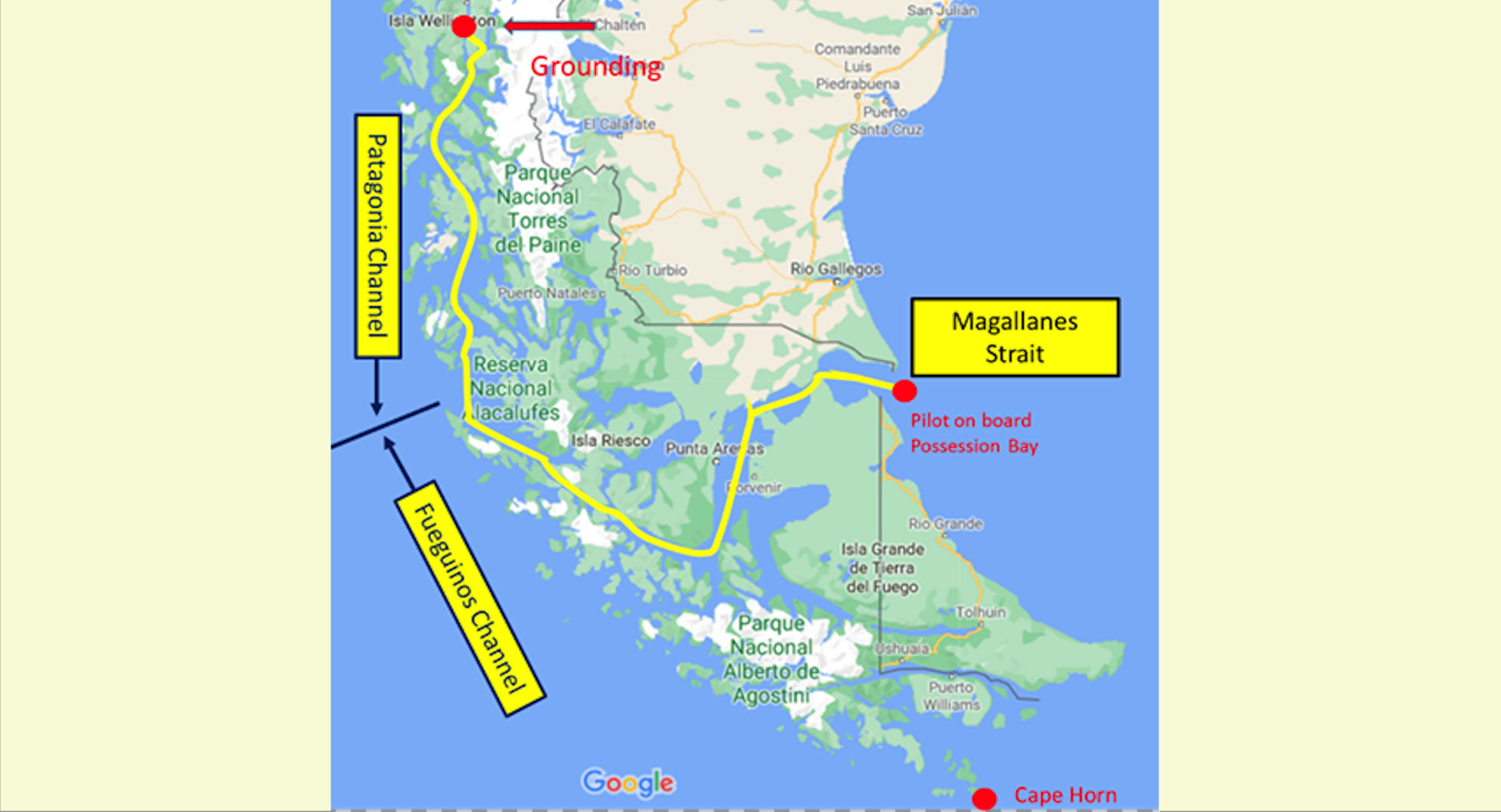

Summary of the incident2: the grounding of the Torepo3

The tanker Torepo (DWT 25,602, LOA 171.4m) departed La Plata, Argentina on 30 June 1997 with a cargo of 23,700 tons of gasoline. The destination was Esmeraldas, Ecuador. Three routes were considered: the Panama Canal, Cape Horn and the Magellan Straits. The decision was made to use the shortest route: the Magellan Straits.

At this point the vessel did not have charts for the Magellan Straits. Some British Admiralty charts were received at Montevideo, a subsequent port of call, however, it was understood that the pilots would bring with them Chilean charts covering almost all the Magellan Straits.

On 7 July, two pilots boarded the Torepo at Possession Bay, the entrance to the Magellan Straits. The vessel then entered the straits as the pilots used the distance index and other items (passage plan included) brought with them. Consequently, no detailed passage plan was prepared for the vessel’s voyage through the Magellan Straits.

On 9 July, while in the Patagonian Channels, the vessel failed to alter course at the point where this move was planned and instead remained on a straight course. The vessel then ran aground at Wellington Island. At that time, there were four people on duty on the bridge: a pilot, the chief officer, a cadet and the helmsman.

The claimant (cargo owner) raised many questions concerning the inadequacy of the passage plan and negligence of the vessel’s Master and officers. The Court’s judgment rejected any deficiency involving seaworthiness (responsibility of the Shipowner) and concluded that the cause was negligent navigation by the pilot and the chief officer.

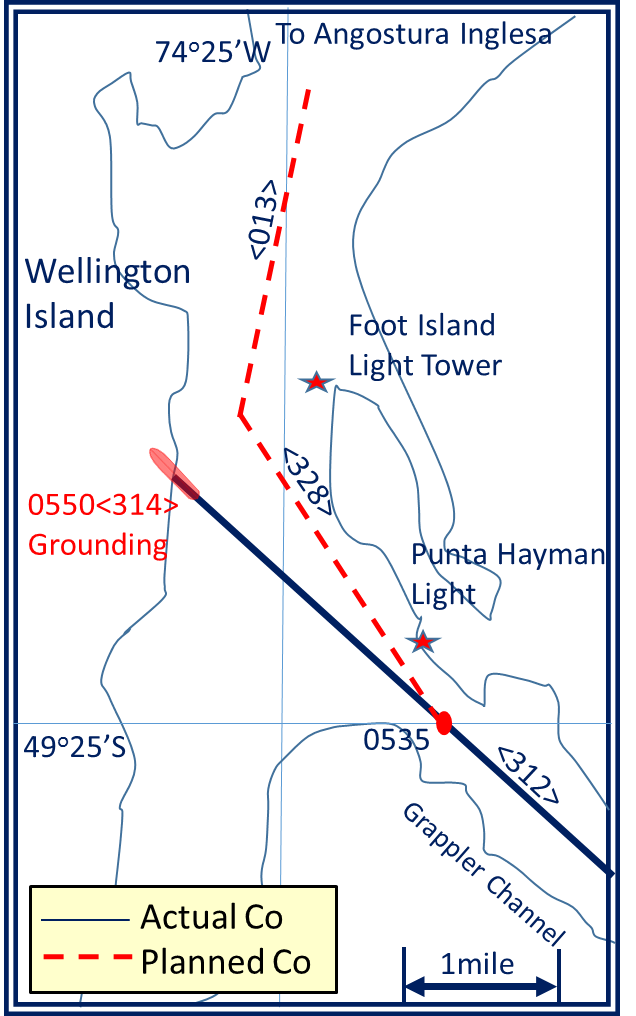

Timetable of the grounding:

05:30 The Torepo approaches the northern end of Grappler Channel, course 312 degrees.

05:35 The pilot asks to reduce the engine from full ahead to slow ahead near Punta Hayman. Based on the planned route using the Chilean chart, the vessel was to alter course to 328 degrees off Punta Hayman and then alter course to 013 degrees off Foot Island. The pilot did not alter course to 328 degrees and remained on 312 degrees.

05:50 The Torepo ran aground at Wellington Island on a heading of 314 degrees.

Figure 1 Route of the Torepo (1)

(Prepared using Google Maps)

Figure 2 Route of the Torepo (2)4

Key points

a) The passage plan

The claimant (cargo owner) made the following statements regarding the passage plan:

- There was no passage plan in place to assist the officer of the watch (OOW) or to encourage him to actively monitor the progress of the vessel.

- The ship’s Master possessed a flawed attitude towards passage planning in general and passage planning whilst under pilotage.

In addition, the claimant stated that the passage plan was negligent as it omitted the following:

i) a notation that the vessel would be approaching the next alteration off course when the Foot Island light became visible;

ii) a range line showing the closest permissible distance when off Wellington Island – this line would show when to abort the passage plan;

iii) a parallel index for the 013 degree track.

The Court concluded: “…passage planning is not science. There was inevitably an element of judgment as to what annotations needed to be added to the charts. I certainly accept that the passage plan would have been improved by the addition of the three matters referred to. But it must be remembered that the passage was not prepared by the Master or officers of Torepo whose expertise in this field is criticized by the claimants. It was prepared by pilots who had regularly taken vessels through the Patagonian Channels with no recorded difficulty”.5

This exchange of views is significant. The three points raised by the claimant are fundamental elements in the preparation of a passage plan. For the Libra accident, the annotation of the Notice to Mariners and the no-go area on the chart were also the basis for preparing the passage plan. Both incidents are therefore linked to the failure to include fundamental items in the passage plan.

It is also worth noting that there are big differences in the responsibility of the ship’s owner (carrier) and the recoverability of contributions to General Average from the cargo interests.

b) What are the reasons for these differences?

The principal reason is the due diligence of the Shipowner (management company).

Section 5 (5.1.1 and 5.2.8) of the Navigational Procedures Manual of the Shipowner contains a clear requirement that: “…the planning should include any passage through pilotage water.” The Bridge Procedure Guide is another extremely useful manual, detailing procedures that should be observed.

The SMS manual that is currently used onboard ships includes similar procedures and instruction. Ships must strictly comply with the directives in these manuals and other publications. Moreover, frequent visits to ships and internal audits are needed to verify compliance and ensure that personnel are committed to the necessary due diligence.

c) Management by the ship’s Master

The claimant (cargo owner) criticized the management of the ship’s Master:

“The Master’s flawed attitude towards the passage planning was compounded by a flawed attitude towards the responsibilities of the vessel when under pilotage. By the reason of the Master’s flawed attitude, he was not a suitable person to be in command of Torepo. Hence the vessel was not properly manned”.6

The Master of the Torepo responded to these allegations in detail.

1) Passage plan

a) The Master ordered all necessary charts at Montevideo.

b) The vessel had charts up to the sector where the pilot was on board, including charts for the Cape Horn route, in case this route had been selected.

c) When the Magellan Straits route was selected, the second officer immediately prepared a passage plan.

d) The passage plan was satisfactory even though the number of available documents for the plan was limited.

e) The plan could not be completed or implemented without large-scale charts.

f) The Master was informed that the pilot brought with him the proper large-scale Chilean charts.

g) These charts could be used for implementing the plan as prepared or to review any plan prepared by the pilots.

The Master gave sound advice that the progress of the vessel should be monitored along the planned track by parallel indexing (more detail on this follows). For this, and the above listed reasons, the Master believed that the passage plan was prepared with his best efforts.

2) Standing orders (comprehensive instructions from the Master for navigation)

The Master’s standing orders included the following instructions for areas where the ship was under pilotage and directives regarding the lookout:

a) Navigation with pilot present

“The presence of a pilot does not relieve the OOW from any of his duties and obligations. The OOW must cooperate with the pilot and constantly confirm the vessel’s position and movements. Furthermore, any alterations in course, including wheel orders and engine movements, must be conveyed through the OOW. The OOW must then confirm that every change has been performed correctly. If the OOW has any doubt concerning the pilot’s actions or intentions, he must seek clarification from the pilot and, if still in doubt, notify the Master immediately.”

b) Lookout

The grounding was attributed to the erroneous lookout of the chief officer and was considered negligent navigation. The Master’s standard orders included the following statement concerning the lookout:

“The OOW is responsible for the maintenance of continuous and alert lookout. This is the most important consideration in avoidance of casualties. The keeping of an efficient lookout includes the following: … (c) Identification of slip and shore lights”.

3) Briefing prior to entering the Patagonian Channels

The Master called a meeting of the navigating officers prior to entering the Patagonian Channels to discuss how to deal with the unusual situation of being entirely dependent on the pilot’s charts (there were no large-scale British Admiralty charts for the Patagonian Channels). The Master instructed the officers to use parallel indexing to monitor progress on the charts. In addition, the Master instructed the officers to transfer the vessel’s position to British Admiralty Chart 561 once every hour.

When charts are inaccurate (see note below) and the vessel is navigated either by using radar or visually, the use of the parallel index to confirm that the vessel is not off course in either direction is the safest navigation method.

NB The sailing directions for the Magellan Straits contains the following precautions:

a) There has been no complete survey of the channels;

b) Some headlands may be incorrectly charted and positions may be inaccurate;

c) Buoys and beacons are not reliable.

4) The Master was not on the bridge when the vessel ran aground

The claimant (cargo owner) was critical of the Master’s absence on the bridge when the Torepo ran aground. In the night order book from the day prior to the grounding, the Master had instructed the OOW to call the Master if they were “in doubt.” The claimant believes this instruction was not appropriate.

The Master responded to the claimant’s criticism explaining that, further to a discussion with the pilot, he determined that the Angostuna Inglesa (located after the location of the grounding) was an area of critical navigation that required the Master on the bridge. The area where the grounding actually occurred was not believed to be one that required the presence of the Master on the bridge. It was considered, therefore, that his absence when the grounding took place was not negligence on the Master’s part.

Closing

1) Judgment

The Court concluded “the claimants (cargo owner) … failed to establish that the casualty was occasioned by causative unseaworthiness.”

Even when the vessel ran aground there was evidence that the its seaworthiness was maintained, and therefore the ship’s owner was not responsible for this accident. The cause of the accident was determined to be due to the inadequate lookout of the pilot and the chief officer regarding the vessel’s course. In this incident, contributions to General Average from the cargo owners succeeded because the cause was classed as negligent navigation by these two individuals. It was held that there was no breach of the contract of carriage by the carrier.

Regarding the inadequate lookout (negligent navigation) of the chief officer, the Court confirmed that there was no negligence concerning this officer’s activities until 05:35, 10 minutes before the Torepo ran aground.

2) Conclusion

Although the Torepo case was referenced in the CMA CGM Libra case, it was concluded that there was no lack of due diligence by the carrier in providing the Torepo with the available large-scale charts. There was also no failure by the Master before the commencement of the voyage and hence no breach of due diligence to make the Torepo seaworthy. For these reasons, the Court held that the two cases – the Torepo and the CMA CGM Libra – were distinctive from each other.

Shipowners (management companies) must provide their ships with the appropriate manuals and other publications for navigation. In addition, the owner must confirm that vessel operations comply with these publications to prevent inappropriate activity, carelessness and other problems when the vessel is under way. The owner also needs to monitor the vessel’s performance by conducting suitable internal audits and visiting the vessel periodically for inspections. They should provide guidance and instruction as necessary.

Regarding the Torepo, the Master, who was the representative of the Shipowner, complied with all documents concerning the vessel’s operation and performed his duties in the spirit of good seamanship. As a result, we can conclude that the Master’s performance and bridge management were proper.

It is apparent, therefore, that the Master has enormous responsibility serving as the representative of the Shipowner. The Torepo incident raised important questions about the responsibility of the owner of the vessel, resulting in the rejection of the allegation that the accident happened because of a defect affecting the vessel’s seaworthiness.

----------------

1“Passage Planning and Seaworthiness”, Captain Hiroshi Sekine, Thomas Miller (2020)

2Grounding of the Torepo, (2002), 2 Lloyd's Rep. 535 THE TOREPO EWHC 1481 (Admlty)

3“Is Grounding Negligent Navigation or Vessel Unseaworthiness?” Ryoji Miyawaki. Commentary on Recent Maritime Verdicts (Edition III), Institute of Maritime Law, Waseda University

4Prepared using Figure 3: Map of Patagonia, in “Is Grounding Negligent Navigation or Vessel Unseaworthiness?”, Ryoji Miyawaki. Commentary on Recent Maritime Verdicts (Edition III), Institute of Maritime Law, Waseda University.

5Grounding of the Torepo, (2002), 2 Lloyd's Rep. 535 THE TOREPO EWHC 1481 (Admlty)

6Grounding of the Torepo, (2002), 2 Lloyd's Rep. 535 THE TOREPO EWHC 1481 (Admlty)