Introduction

Before departure, a ship’s officer has an obligation to establish a voyage plan and confirm that the plan ensures a safe voyage and arrival at the destination with no problems. Guidelines for the preparation of voyage plans are in IMO Resolution A 893(21) – Guidelines for Voyage Planning.

These guidelines contain the following four steps. All of these steps must be performed thoroughly in order to determine a proper voyage plan. Shortened explanations of these steps are shown here because detailed information about the steps is provided in the SMS manual that is kept on all ships.

1. Appraisal

Appraisal of the voyage is performed after collecting all information involving the planned voyage or route. This process identifies risks involving the proposed voyage prior to departure and, as needed, incorporates this information in the voyage plan.

2. Planning

Using the largest amount of information possible that was obtained for the appraisal stage, prepare a detailed voyage plan that extends from the departure berth to the destination berth, including sections where a pilot will be on the bridge.

3. Execution

If the voyage plan is approved, the plan must be executed by using it as the basis for specific actions. There may be times when the plan will have to be revised to reflect changes in various factors involving the voyage while under way. If revisions are made, the voyage plan must be appraised again and the revised plan must be executed.

4. Monitoring

Thorough and constant monitoring is required to confirm that the ship is on the course in the voyage plan approved prior to departure. This is the most important duty of officer of the watch. Several methods must be used to confirm the current status of the ship. If this oversight process reveals that the ship is not following the voyage plan, the master must be notified and corrective measures taken.

Case studies of accidents caused by inadequate voyage plans

A voyage is completed by implementing the four steps outlined earlier in accordance with the voyage plan established by the officer. In particular, crew members must be aware that a significant error or oversight in even one of these steps can result in an accident. This section explains accidents caused by errors or negligence in one or more of these steps.

1. Inadequate appraisal

Grounding of the CMA CGM Libra

The appraisal of a voyage requires a large volume of information, including equipment on the bridge, external information such as meteorological data, the status of the ship and many other items.

On May 18, 2011 the containership CMA CGM Libra (130,000 tons, 353 meter length) departed Xiamen, China. The second officer prepared the voyage plan but information about shallow areas outside the departure channel was not written on the chart. In addition, there were no “no go area” entries on the chart, including the shallow area where the accident happened. Although the master approved the voyage plan, he was not aware of this information about the shallow areas. Believing that an area outside the planned course was safe (deeper than shown in the chart), he took the ship off the course and ran aground. This accident demonstrates that the voyage plan prepared prior to departure was not appropriate and, as a result, the ship was not seaworthy. More information about this accident is on the website below (Note 1).

An enormous amount of information is used during the appraisal stage and even one insufficiency can result in a major accident. As a result, this accident highlighted a significant problem for seafarers.

Note 1: Preparation of voyage plan and seaworthiness

2. Inadequate planning

Grounding of the Kaami1

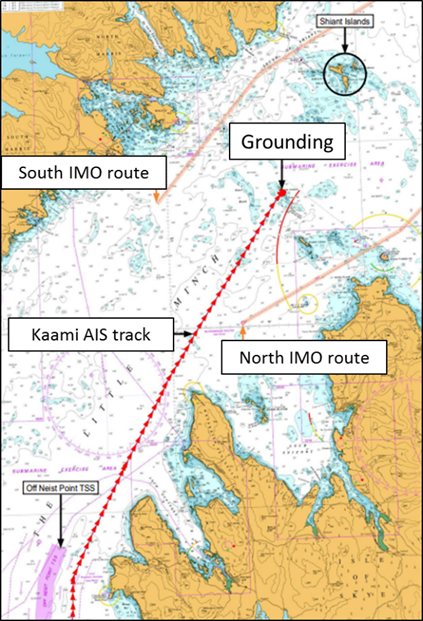

On March 23, 2020, the general cargo vessel Kaami (2,715 tons, 89.95 meter length) was on a course from Drogheda, Ireland to Slite, Sweden when the ship ran aground on Stgeir Graidach shoal in the Little Minch on the west coast of Scotland. The master selected a course that included this shoal by relying on experience from a voyage on a different vessel and did not use the route recommended by the IMO.

This accident was the result of the establishment of an erroneous course when the voyage plan was created. The primary cause was the failure to use a sufficient volume of data during the appraisal step of the voyage plan preparation process. Furthermore, there were many deficiencies and oversights involving the execution and monitoring of the plan. (Figure 1, Figure 2)

Figure 1 Grounding position

Figure 2 Kaami’s track

Particulars of the accident

At Drogheda, the master carried out chart updates on the ship’s ECDIS and planned the voyage to Slite because the chief officer (C/O) was overseeing cargo operations. At 2030 on March 21, 2020, the Kaami (draughts of 4.90m forward and 5.40m aft) departed Drogheda and proceeded up the Irish Sea through the North Channel. The weather deteriorated after the ship departed. There was a south-westerly Beaufort force 6 to 9, a very rough sea, and total cloud cover with good visibility.

Just before 2300, the C/O and an able seaman arrived on the bridge to relieve the master. At 0058, the C/O notified the Coastguard that the ship was approaching reporting point “F,” which is the start of the IMO recommended northerly route. However, the Kaami did not use the recommended route and instead used a route about one nautical mile north of Eugenie Rock, which was the planned track.

At 0135 a crewmember of the fishing vessel Ocean Harvest contacted Kaami on VHF radio to warn that Kaami was heading into shoal waters. The C/O replied promptly and thanked the Ocean Harvest for the information. A few minutes later, the Kaami’s C/O used the autopilot to alter course 10˚ to starboard at waypoint 19 in accordance with the voyage plan. At 0141, the C/O and watch felt two heavy impacts as the ship ran aground.

Analysis of the causes that directly contributed to the accident

The Kaami ran aground because the voyage plan was configured to take the ship over an area with dangerous obstacles. The master had passed through this area before. When preparing the voyage plan, he relied on his previous experience concerning the weather, sea conditions and other considerations. In addition, he used only the Kaami’s electronic navigation chart (ENC) data. The appraisal step prior to preparing the voyage plan is obviously an integral part of the voyage plan preparation process. As is explained later, this was clearly insufficient. Moreover, insufficient monitoring activities, including the ECDIS settings and how the ECDIS was used, were a major cause of the accident.

The accident was the result of a number of failings during both the appraisal and monitoring steps. Failure to properly use the ECDIS in particular was a major cause of the grounding. Problems involving use of the ECDIS and brief explanations are as follows.

1) No setting of safety contour

Kaami departed with a maximum draught of 5.40 meters but the safety contour was still at the previous setting of 5.00 meters. Determining the under keel clearance (UKC) is essential for setting the proper safety contour, but this was not done on the Kaami. Furthermore, the safety management system of the company managing the Kaami did not have any specific provisions concerning the UKC.

2) Improper use of the ENC

The electronic chart in use when the ship ran aground was missing part of the route recommended by the IMO.

3) Waypoint input

When the master prepared the voyage plan, he used the mouse to drop waypoints on the ENC. This makes it possible to easily enter the route on the ECDIS. However, this route took the Kaami over a hazardous (shallow) area. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) has issued a strong warning concerning the need to use an ENC at the proper scale and to perform visual confirmations.

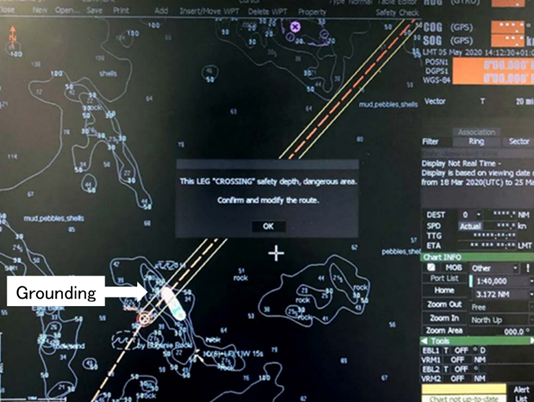

4) Safety check (Figure 3)

The Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) was unable to ascertain if the ship used the ECDIS safety check function. When a safety check was conducted after the accident, it revealed 479 errors (hazards) on the route. The ECDIS safety check function is an extremely effective way to supplement visual checking.

Figure 3 The ECDIS safety check display

the warning shown below is displayed in the center.

“This Leg “CROSSING” safety depth, dangerous area, Confirm and modify the route”

5) Look ahead sector and vector

The Kaami was not using the look ahead sector and vector, which issues a warning when the ship approaches a safety contour or other hazard. If this function had been selected, a safety contour alarm would have activated on the ECDIS three minutes before crossing the contour line.

Lessons from this accident

When the voyage plan was prepared, the determination of the route was made in a simple manner. However, there is clearly a close relationship with errors and negligence in each stage of the voyage appraisal, implementation and monitoring steps.

In particular, the preparation of a voyage plan (input of a voyage route) by ECDIS, as pointed out in this case, makes it possible to easily draw a voyage route by dropping (setting) a waypoint on the screen with the mouse.

The use of the ECDIS creates the possibility of skipping some steps of the proper voyage planning process. Officers must always be aware of this problem, which is an issue involving the use of any type of high-tech equipment.

3. Improper execution of a voyage plan

Grounding of the Inazuma2

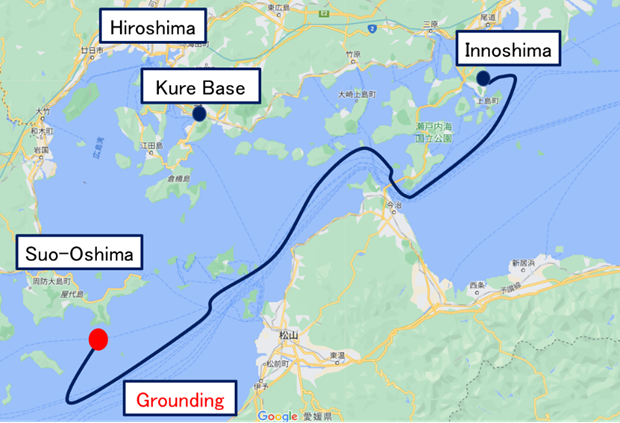

At 1210 on January 10, 2023, the Marine Self Defense Force destroyer Inazuma (4,500 tons, 151 meter length, crew of 190) ran aground on the Sengai shallows, which is about 5km south of Suo-Oshima Island in Yamaguchi prefecture. This location is marked by the Sengai Shoal beacon. (Figure 4)

On the morning of January 10, Inazuma departed the Innoshima Island shipyard for a test run after completing maintenance work. The ship planned to turn back near where the grounding occurred in order to return to the MSDF base at Kure. The screw apparently hit a rock or other objects and there was a small oil leak. Repairs are expected to take a few years and cost about 4 billion yen.

Figure 4 Location of the grounding of the Inazuma

(Google map background)

Figure 5 Estimated route of the Inazuma and location of grounding

(Google map background)

(Prepared by the author based on media reports)

Announcement of result of the investigation

On May 9, 2023, the MSDF announced that the cause of this accident was improper safety management that included navigation orders without the captain and others being aware of this shallow area. The announcement was made at a press conference and included the following key points.

After the Inazuma completed testing at about 1135, the captain ordered a revision to the voyage plan but failed to take the following safety measures.

- Changed the ship’s route without confirming the safety of the route.

- Officers responsible for navigation did not check the chart.

- There were several warnings from the command information center of shallow water but this information did not reach the captain and others on the bridge.

- Prior to departure, there was no meeting to confirm the safety of the route or the region where the Inazuma was going.

The MSDF announced five preventive measures that include the following two actions.

- Reexamination of the process used to train officers to become captains of ships

- Studies regarding a communication system that facilitates the sharing of required information

Analysis

Details concerning this accident are limited because a press conference was used to announce the results of the investigation. This section attempts to analyze this accident from the standpoint of the operation of commercial ships. Bridge management on a military ship differs significantly in many ways, such as the number and roles of bridge personnel, the involvement of other crewmembers, and equipment on the bridge. The following are two examples of these differences.

- Transmission of information from the command information center (not located at the bridge)

The command information center is a supplementary source of information about other ships and hazards. Information is transmitted to the bridge by using a communication system.

- Division of roles of bridge personnel

The bridge of a military ship includes the captain, navigator and many others, each with a clearly defined role. For example, the navigator receives information from subordinates on the bridge and at the command information center.

Lesson learnt : Change of voyage plan during voyage

The crew of a ship frequently revises a voyage plan while under way for a variety of reasons. Changing the voyage plan requires the same four steps that are used to prepare the original plan: appraisal, planning, execution and monitoring. On the Inazuma, the captain made a sudden change in the voyage plan. However, when a change is necessary, an appraisal of the new plan must be conducted. This process includes checking for shallow areas and other hazards in the new course, positions of nearby ships, and other considerations. In addition, as part of bridge resource management, the captain and navigator must constantly confirm the receipt of advice and other input from subordinates. This accident is an example of the result of a defective process used to determine a voyage plan as well as poor bridge management.

4. Improper monitoring of a voyage plan

Grounding of the Royal Majesty3

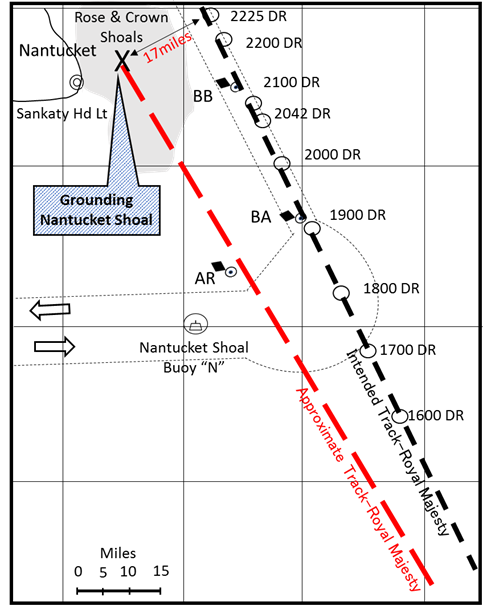

The passenger ship Royal Majesty (32,396 tons, 173.16 meter length) ran aground on the Rose and Crown Shoal at about 2225 on June 10, 1995. The ship was on route from Bermuda to Boston, Massachusetts. The shoal is approximately 10 miles east of Nantucket. Although the accident caused deformation of the ship’s double bottom hull, there was no penetration or cracking and no fuel oil was spilled. Damage to the ship was estimated at $7 million.

Particulars of the accident

One hour before the scheduled departure time of 1200 on June 9 from the port in Bermuda, the navigator performed tests of navigation equipment (compasses, repeaters, radar, NACOS 25, GPS, Loran-C) and confirmed that everything was operating normally. The navigator stated that when the Bermuda pilot left the ship (about 1230 on June 9), he compared the position data of the GPS and Loran-C and confirmed that the two positions within about one mile of each other.

At 1000 on June 10, the watch changed and the navigator and two quartermasters were on duty. The navigator maintained a course of 336˚ and a speed of 14.1 knots. At 1600 the watch changed and the C/O relieved the navigator.

The C/O used GPS data to check the ship’s position once every hour during his watch and used Loran-C as a backup system.

At about 1920, the ship passed a radar target that was believed to be the BA buoy, which was on the port side at a distance of 1.5 miles. However, visual confirmation of the target was not possible because of glare on the ocean surface caused by the setting sun. The master was notified that the ship had passed the BA buoy.

At 1000 on June 10, the watch changed and the navigator and two quartermasters were on duty. The navigator maintained a course of 336˚ and a speed of 14.1 knots. At 1600 the watch changed and the C/O relieved the navigator.

The C/O used GPS data to check the ship’s position once every hour during his watch and used Loran-C as a backup system.

At about 1920, the ship passed a radar target that was believed to be the BA buoy, which was on the port side at a distance of 1.5 miles. However, visual confirmation of the target was not possible because of glare on the ocean surface caused by the setting sun. The master was notified that the ship had passed the BA buoy.

At 2000, the second officer and two quartermasters relieved the C/O.

About 2030, the lookout on the port bridge wing reported to the second officer the sighting of a yellow light off the ship’s port side. The second officer acknowledged the report but took no action.

Shortly after the yellow light was sighted, both starboard and port lookouts reported sightings of several red lights on the port side of the ship, but the second officer took no action.

At 2145, although the BB buoy had not been sighted, the second officer reported to the captain that he had seen it. The report was based on the second officer’s belief that the ship was on course and that perhaps the radar did not reflect the buoy.

Shortly after 2200, the port bridge wing lookout reported the sighting of blue and white water dead ahead. The second officer acknowledged the information but no action was taken. The port lookout subsequently reported that the ship had passed through the blue and white water. About 2220, the ship suddenly veered to port and then sharply to starboard and heeled to port. The master ran to the bridge and confirmed that the ship had run around. The master checked the GPS and Loran-C position data and for the first time realized that there was a difference of at least 15 miles.

Figure 6 Course of the Royal Majesty

(prepared by the author based on the investigation report)

Analysis

The Royal Majesty had an integrated bridge system (NACOS 25) and GPS was selected as the source of position data for this system. After the accident, an examination of the GPS antenna and receiver revealed that the antenna cable had separated from the antenna connector. As a result, the GPS receiver had been sending to the NACOS 25 autopilot position data determined by dead reckoning rather than by signals from satellites. Longitude data was calculated by using dead reckoning and there were no corrections to reflect the effects of the wind, tide or ocean currents. Over time, an east-northeasterly wind and sea had pushed the ship to the west-southwest, eventually resulting in an error of 17 miles.

Failures and errors involving monitoring

The crew’s failure to detect for more than 34 hours that the ship was not using GPS data raised serious concerns about the performance of the watch officers and the master. The C/O and second officer were on watch prior to the grounding and failed to realize that the Royal Majesty was not following the voyage plan despite several indications of trouble. This is gross negligence.

1) Master

The master visited the bridge frequently and asked the C/O and second officer to visually confirm the sighting of the BA buoy and BB buoy. Therefore, the master took reasonable actions to confirm that the ship was on course. However, he did not ask for a crosscheck of the GPS and Loran-C position data and did not perform a comparison of his own. Consequently, he was relying on the automated navigation system with the other officers.

2) C/OThe buoy detected by radar at about 1900 was the AR buoy that marks the location of a sunken ship about 17 miles to the west of the Royal Majesty’s intended route. Although the buoy could not be visually identified, a positioning crosscheck (GPS and Loran-C) would probably have made the C/O aware of the navigation error.

3) Second officer

The second officer gave a false report to the master about the sighting of buoys. Furthermore, he took no action despite receiving reports from the lookout of unusual sightings near the ship and on the ocean surface.

Lessons learned from this accident

The direct cause of this accident is the loss of GPS position data. Moreover, the navigator failed to crosscheck the ship’s location by using two methods that are used when GPS position data is lost. However, as was explained earlier, all members of the bridge team were guilty of significant negligence as well as numerous small errors. The bridge team was unable to sever the resulting error chain and the result was the grounding of the ship. This accident underscores the importance of the frequent use of suitable measures to monitor a voyage in order to have accurate information about the status of the voyage at all times.

Closing message

This report explains issues involving the four voyage plan preparation steps (appraisal, planning, execution, monitoring) by using examples of accidents involving these plans. The causes of these accidents demonstrate the close relationship among two or more of these steps. The conclusion is that the completion of a safe voyage requires the use of all available resources by the bridge team for every voyage. Furthermore, no part of the prescribed procedure should be omitted during the preparation of the voyage plan.

< Reference >

1. MAIB REPORT NO 7/2021

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60acb4bd8fa8f520bde56d16/2021-07-Kaami.pdf

2. Sankei Newspaper, TBS News Dig, Mainichi Newspaper , dated 9th May 2023

3. NTSB/MAR-97/0l

https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/mar9701.pdf